Surface Water

Surface water runoff in the WMA strongly correlates with the areas of high

rainfall in the Drakensberg and Soutpansberg. Some 45% of the total surface

runoff from the WMA flows down the Klein and Groot Letaba Rivers (most of which

is contributed by the Groot Letaba River) and a further 45% is contributed by

Luvuvhu and Mutale Rivers.

The relatively flat, low rainfall Lowveld areas generate very little runoff, with

the Shingwedzi and Lower Letaba River catchments jointly contributing a mere 10%

of the streamflow in the WMA.

Lake Fundudzi is the only natural lake in the WMA. This was formed by an ancient

landslide across the Mutale River. There are no large wetlands in the WMA. Both

low and flood flows in the rivers are of great importance to the Kruger National

Park, with a particularly important ecosystem which exists in the Pafuri Flood

Plain along the Limpopo River.

Afforestation in the upper reaches of the Groot Letaba, Luvuvhu and Klein Letaba

Rivers (in descending order of magnitude) result in relatively large reductions

in streamflow. Substantial infestations of invasive alien vegetation are found

in the Luvuvhu and Groot Letaba River catchments. Cultivation practices and

over-grazing also impact on the surface runoff, sediment loads as well as

infiltration to groundwater. However these impacts have not yet been reliably

quantified. The natural mean annual runoff (MAR), and the estimated requirements

for the ecological component of the Reserve are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Natural Mean Annual Runoff and Ecological Reserve (million m³/a)

|

Sub-Area |

Natural MAR |

Ecological Reserve |

|

Luvuvhu/ Mutale |

520 |

105 |

|

Shingwedzi |

90 |

14 |

|

Groot Letaba |

382 |

72 |

|

Klein Letaba |

151 |

20 |

|

Lower Letaba |

42 |

13 |

|

Total |

1185 |

224 |

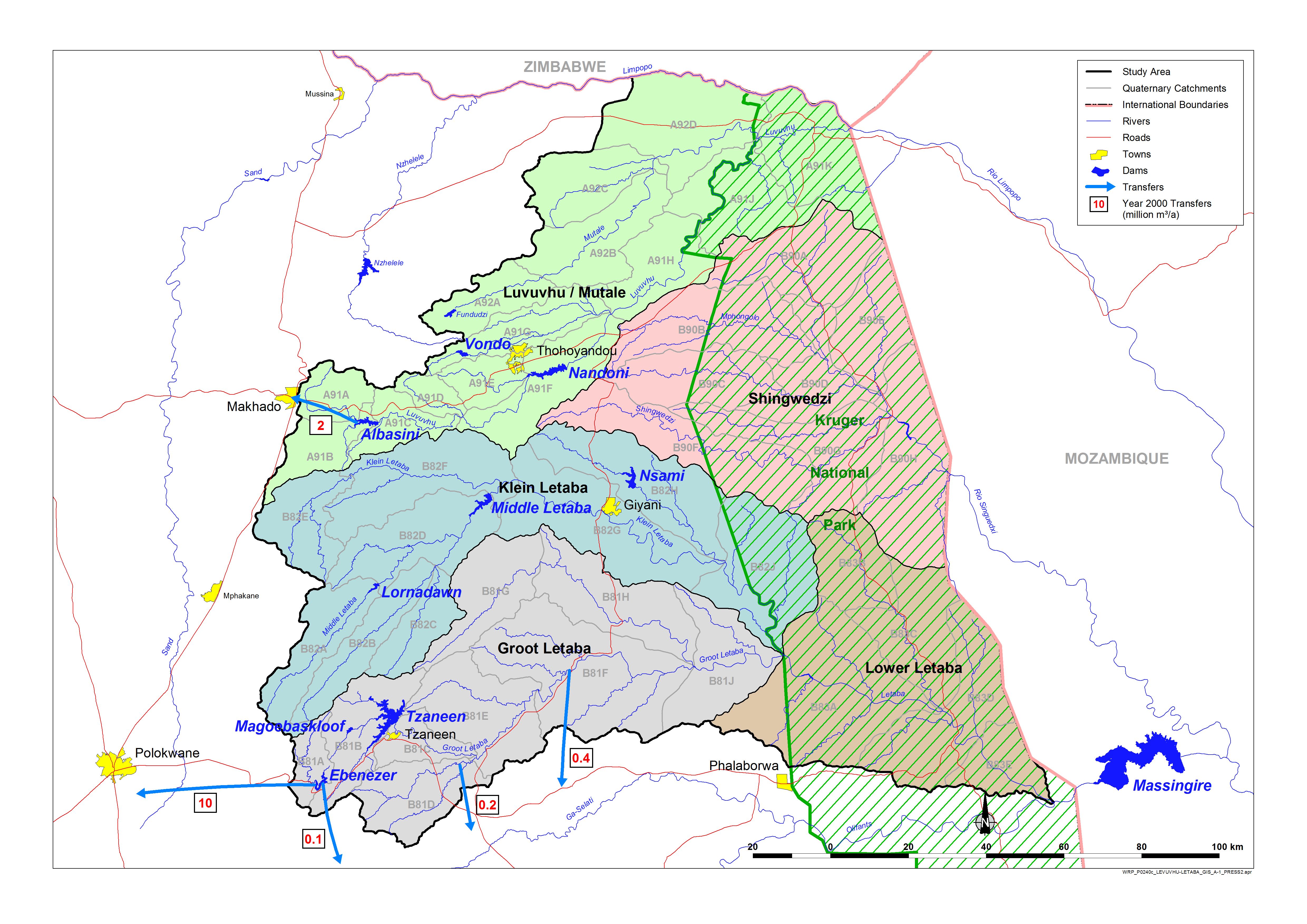

Water Supply Infrastructure

The surface water resources, which naturally occur in the WMA, have for the most

part been highly developed and the water is fully utilised, with little

opportunity for additional development. The one exception is the Mutale River

catchment. The main storage dams in the WMA are:

Luvuvhu/Mutale Sub-area

Vondo, Albasini, Damani, Mukumbane and Tshakhuma Dams located in the upper

tributaries of the Luvuvhu River. The recently completed (2004) Nandoni Dam in

the Luvuvhu River is already storing water.

Klein Letaba Sub-area

Lorna Dawn, Rietspruit, Middle Letaba and Nsami dams are located in the catchment

of the Klein Letaba River.

Groot Letaba Sub-area

Dap Naudé, Ebenezer, Magoebaskloof, Vergelegen Merensky and Tzaneen Dams are

situated in the upper reaches of the Groot Letaba River catchment.

Shingwedzi and Lower Letaba Sub-areas

There are no major dams in these sub-areas because of the limited water resources

and the non-availability of suitable sites. Some small dams have, however, been

constructed in the Kruger National Park for game watering. Of these, the most

notable are the Kanniedood Dam on the Shingwedzi River and the Engelhard Dam on

the Letaba River.

A number of schemes were constructed for the transfer of water to neighbouring

WMAs. The largest transfers are from Ebenezer Dam and Dap Naudé Dam to Polokwane

and from Albasini Dam to Louis Trichardt (Makhado Local Municipality), both in

the Limpopo WMA. There are small transfers from the Groot Letaba catchment for

mining near Gravelotte and to rural villages in the Olifants WMA.

A number of options for the possible further development of surface resources

have been investigated. The raising of the existing Tzaneen Dam, construction of

the proposed Nwamitwa Dam on the Groot Letaba River and a possible dam on the

Mutale River are considered feasible options. Storage on the Letsitele River has

been found to be unattractive.

FIGURE 2: LUVUVHU AND LETABA WMA SUB-AREAS AND TRANSFERS TO ADJACENT WMAs

Groundwater

For many water users, groundwater constitutes the only dependable source of water

and its utilisation is of major importance in the Luvuvhu/Letaba WMA. A large

proportion of the rural domestic and stock watering requirements are supplied

from groundwater for most of the rural settlements and villages in the WMA.

Groundwater is also used for game watering. Substantial quantities of

groundwater are abstracted for irrigation purposes in the upper Luvuvhu River

catchment and upstream of the Middle Letaba Dam. In total some 15% of all

available yield from water resources in the WMA is from groundwater.

There is uncertainty regarding the quantity of groundwater abstracted upstream,

downstream and in the vicinity of Albasini Dam as well as about the reliable

yield and abstraction from the dam. There is a possibility that a strong

inter-dependence may exist between surface flow and groundwater where much of

the base flow in the river is from groundwater.

Over-exploitation of the groundwater resource occurs at some locations in the

WMA, notably in the vicinity of Thohoyandou, at Gidiana and possibly downstream

of Albasini Dam. The quality of groundwater in the WMA is generally good

particularly in the mountainous areas. Water of high mineral content occurs in

some of the drier parts. There are no records of significant pollution of

groundwater.

Water Availability and Requirements

Luvuvhu/Mutale Sub-area

The water resource of the Luvuvhu and Mutale catchments is surprisingly large

considering the limited storage. This is due to the high rainfall in the

Soutpansberg, which results in high run-of-river yields in both catchments.

Water requirements in the Luvuvhu catchment, (year 2000) dominated by irrigation,

have exceeded the available resource, while the water use in the Mutale (year

2000), again mostly irrigation, is approximately in balance with the resource.

The recent completion of the Nandoni Dam resulted in a surplus of 37 million m³/a

becoming available in the Luvuvhu catchment.

There is a high but unmonitored groundwater use in the Luvuvhu catchment and it

is not certain how this groundwater use impacts on the surface water resource.

Klein Letaba Sub-area

Most of the water use is for irrigation, while domestic use is also significant.

Original estimates of the yield of the Middle Letaba Dam were much higher than is

now believed to be the case. This, together with rapidly increasing supply from

this dam to meet domestic requirements has resulted in irrigators downstream of

the dam experiencing serious deficits, to the extent that they have ceased

operating. These irrigation schemes are the target of the irrigation

revitalisation project, but there is no water available for this purpose.

Water use in Giyani is very inefficient and wasteful. Water conservation and

demand management measures are soon to be implemented in this area.

Groot Letaba Sub-area

Substantial run-off is generated in the upper reaches of the catchment but

forestry has a significant impact on this.

Dams such as Tzaneen, Ebenezer and Magoebaskloof result in substantial utilizable

yield in this catchment.

The catchment as a whole is in deficit although users upstream of the Tzaneen Dam

enjoy a relatively high level of assurance while users downstream experience

shortages.

Irrigation has developed and expanded to fully utilise the water resources but

this is prior to the calculated allowance required for the Ecological Reserve.

These are mostly perennial high-value crops. Financial losses during droughts

have resulted in more efficient water use by irrigators. Current schemes are

reportedly very efficient and well managed. There might be limited scope for

further improvements.

Lower Letaba Sub-area

The Lower Letaba sub-area is situated downstream of the Groot Letaba and Klein

Letaba sub-area and falls entirely within the Kruger National Park. This

sub-area therefore receives all the water flowing out of the Groot Letaba and

Klein Letaba sub-areas (see Figure 2.).

For all practical purposes, no sustainable yield is derived from runoff in

the Lower Letaba sub-area.

The only water requirements are to supply the

ecological requirements in this sub-area.

Game watering and domestic

requirements for the rest camps in the park are supplied mostly from

groundwater.

The sub-area is ecologically important because it is situated

mostly in the Kruger National Park.

The ecological requirements are not being

met in full due to over-utilisation of the resource in the upstream sub-areas

where the majority of the flow originates.

Shingwedzi Sub-area

For all practical purposes, no sustainable yield is derived from surface flow in

the Shingwedzi catchment. There could be small yields derived from small farm

dams but these would probably be of very low assurance due to low and variable

rainfall.

Water use in the catchment is negligible, so return flows do not contribute to

the water resource.

The sub-area is situated mostly in the Kruger National Park, water requirements

are limited and these are met from groundwater. The area is essentially in

balance.

No management intervention is required in this catchment.

Additional domestic requirements, should they arise, can be met from groundwater.

|